We left off with the bonnet rouge, or the red cap of liberty, being adopted as an accessory of the French Revolution that represented the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

But what happens when you assign so much political significance to an article of clothing? The meaning shifts, and soon the bonnet rouge came to represent something else altogether. What began as a symbol of resistance to oppression, a sartorial call to arms, soon became a form of protection: moderates took to wearing the bonnet rouge during the Reign of Terror to mask their true political leanings, lest they be denounced as aristocrats and sentenced to the guillotine. Even Louis XVI donned the Pyrigian cap during the invasion of the Tuilleries Palace by Parisian sans-culottes in 1792, as illustrated in this reworked engraving (right).

True revolutionaries soon used the bonnet rouge as permission to act like dicks in the name of overcoming oppression:

From the reports of police agents during 1792-93, it becomes clear that certain wearers of the bonnet rouge acted as if they had been given special license to commit minor crimes in the name of the Revolution. With the symbolic headdress on their heads, truculent individuals caused trouble in the streets of Paris, picking quarrels with those who were not wearing the red cap of liberty. One report claimed that these bonnets rouges “believed that they had the right to commit a thousand extravagances in the streets, in the cafes, and in the cabarets. [i].

Robespierre himself became wary of the bonnet rouge’s power. Together with Jerome Petion, the Mayor of Paris, he “successfully opposed a motion that would have made the liberty cap compulsory wear for speakers and members of the Jacobin Club” [ii]. Ironically, the man who took the Revolution to its extreme also worked to keep the radicalism of his party in check, and he did so through limiting the use of the bonnet rouge. Robespierre need not have feared the widespread use of the bonnet rouge, however, as it became so popular that not all citizens could afford one. This points to another irony of revolutionary fashion:

Far from being a symbol of universal kinship, the bonnet rouge became another mark of exclusivity, enabling some members of society to act like petty tyrants in the streets. People began to complain that it was not possible for everyone to afford a bonnet rouge – merchants were making such a profit from the sale of these so-called ‘bonnets of the people’ that they had become too expensive. [iii]

The bonnet rouge, which began as a symbol of the egalitarian values of liberty, equality, and brotherhood, ultimately turned into a license to commit petty crimes in the streets and became an exclusionary product. The sans-culottes who donned the bonnet rouge had, in effect, turned into the very thing they had revolted against: the oppressors at the top of a stratified social order.

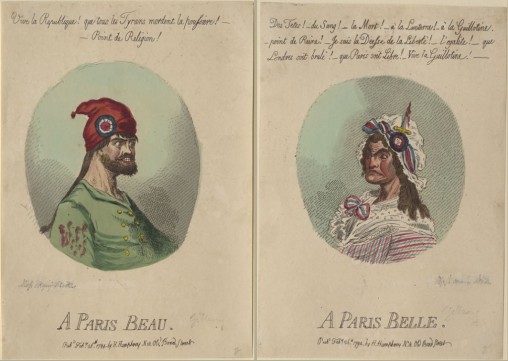

Women, too, were excluded from the acceptable bonnet rouge paradigm. The radical women who did choose to wear it “were considered unnatural and were both feared and ridiculed by men and by more orthodox women. Throughout the Revolutionary period, the bonnet rouge was considered by most people to be a man’s hat and a man’s privilege” [iv]. The original egalitarian connotation of the bonnet rouge, then, only ever applied to men. Go figure.

As with all cycles, though, the bonnet rouge soon fell out of favor following the Thermidorian reaction in 1794. By that time, any sans-culotte still wearing the liberty cap was singled out by the young, hostile, counter-revolutionary Incroyables roaming the streets and looking to settle the score (but more on them later).

The Tricolour Cockade

The tricolour cockade (ribbon rosette) is another Revolutionary accessory that sparked conflict and violence. Patriotic citizens adopted the tricolour cockade within days of the storming of the Bastille, and society at large followed the style shortly after. After the storming of the Bastille, red was added to France’s national colors of blue and white in an attempt by the Marquis de Lafayette “to preserve unity between the monarchy and the reformers” [v]. A cockade in the new national tricolour was a natural symbol for Revolutionary sentiment: “ribbon cockades were already associated with military headdresses earlier in the eighteenth century, and the ornament had connotations of choosing and displaying allegiance to a cause” [vi].

The tricolour cockade (ribbon rosette) is another Revolutionary accessory that sparked conflict and violence. Patriotic citizens adopted the tricolour cockade within days of the storming of the Bastille, and society at large followed the style shortly after. After the storming of the Bastille, red was added to France’s national colors of blue and white in an attempt by the Marquis de Lafayette “to preserve unity between the monarchy and the reformers” [v]. A cockade in the new national tricolour was a natural symbol for Revolutionary sentiment: “ribbon cockades were already associated with military headdresses earlier in the eighteenth century, and the ornament had connotations of choosing and displaying allegiance to a cause” [vi].

While fashionable, worldly women of the day happily incorporated the cocarde nationale into their headdresses and shoes as a stylish, patriotic accessory (though not without an occasional scolding from a sans-culotte for her turning the venerable cockade into a ridiculous “objet de luxe”), the Revolutionary-minded “women of the streets” considered it with no such levity and instead focused “on the wearing (or the absence) of the tricolour cockade in their struggle for recognition as the political equals of men” [vii]. It was contentions between women, in fact, that turned the tricolour cockade into an accessory of disruption and violence.

While fashionable, worldly women of the day happily incorporated the cocarde nationale into their headdresses and shoes as a stylish, patriotic accessory (though not without an occasional scolding from a sans-culotte for her turning the venerable cockade into a ridiculous “objet de luxe”), the Revolutionary-minded “women of the streets” considered it with no such levity and instead focused “on the wearing (or the absence) of the tricolour cockade in their struggle for recognition as the political equals of men” [vii]. It was contentions between women, in fact, that turned the tricolour cockade into an accessory of disruption and violence.

While women may not have received the political equality they felt they deserved, Revolutionary and counter-Revolutionary women alike certainly made their loyalties known through outbreaks of violence in the streets over the tricolour cockade. Police reports include numerous records of disputes that erupted over the wearing, or the refusal to wear, the cockade. One contemporary male witness to such an event writes,

Past Viroflay they met a number of individuals on horseback who appeared to be bourgeois and wore black cockades [indicating monarchic sympathies] in their hats. The women stopped them and made as if to commit violence against them them, saying that they must die as punishment for having insulted, and for insulting, the national cockade; one they struck and pulled off his horse, tearing off his black cockade. [viii]

In an attempt to end the violence, a decree was passed that mandated the tricolour cockade be worn by all women, with escalating degrees of punishment “for each incidence of non-compliance, including ten years of imprisonment for any woman who was found guilty of ‘snatching away’ the cockade of another” [ix]. Unfortunately, the decree provoked further violence rather than assuaged it. Women with counter-Revolutionary sympathies were enraged and humiliated at being forced to wear the cocarde nationale, leading to even more vicious brawls that, in several cases, nearly resulted in death for the target of their fury.

In an attempt to end the violence, a decree was passed that mandated the tricolour cockade be worn by all women, with escalating degrees of punishment “for each incidence of non-compliance, including ten years of imprisonment for any woman who was found guilty of ‘snatching away’ the cockade of another” [ix]. Unfortunately, the decree provoked further violence rather than assuaged it. Women with counter-Revolutionary sympathies were enraged and humiliated at being forced to wear the cocarde nationale, leading to even more vicious brawls that, in several cases, nearly resulted in death for the target of their fury.

Again, irony ensues: a symbol the designed to express unity among the citizens, reformers, and the monarchy only served to drive these factions further apart.

And that’s not all, folks: in Part 3, we’ll examine the violent flamboyance of the Incroyables and Marveilleuses. Stay tuned!

Sources

[i] Shilliam, Nicola J. “Cocardes Nationales and Bonnets Rouges: Symbolic Headdresses of the French Revolution.” Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts 5 (1993): 122. 31 Jan. 2010.

[ii] Shilliam 117.

[iii] Shilliam 123.

[iv] Shilliam 124.

[v] Shilliam 109.

[vi] Shilliam 110

[vii] Shilliam 114.

[viii] Shilliam 109.

[ix] Shilliam 113.

It’s always a treat to be educated in an area outside of one’s expertise – please keep blogging!

LikeLike